Jesse Hines stands behind the register at his Nags Head yogurt shop, chatting with a kid holding a skateboard who doesn’t seem to have any intention of buying anything.

His wife, Whitney, holding their 2-year-old-son Bear, is chatting with an elderly couple in town for the weekend. They may buy a scoop of key lime pie flavor, or chocolate with M&M’s on top, or they may not get anything at all. It doesn’t matter much to the Hineses. They’re focused on the conversations. Jesse and Whitney seem to know everyone who walks through the door, and they know that their visitors come just as much for the warm and familiar welcome as they do for the yummy yogurt flavors and huge variety of toppings on offer.

“It’s kind of like our living room,” Jesse says later, sitting on a picnic bench outside the shop. “People stop in just to say hi all the time. We get really busy with the tourists in the summer, so it’s nice just to have friends come in to chat.”

Jesse and Whitney started up Surfin’ Spoon four years ago, after Jesse’s 11-year career as a professional surfer had come to an abrupt end. A financial squeeze that forced many surf industry sponsors to slash their budgets, concurrent with a hip replacement surgery that couldn’t be put off any longer, prompted the couple to make a new plan for their lives, and a little neighborhood shop like this was something they’d often dreamed about.

“Our house was pretty much like this before we opened the Spoon” Jesse says. “We’d always have people coming over, people crashing for the weekend, whatever. We like company.”

So they decided to turn their natural sense of hospitality and charm into a business. They’d seen similar shops in California, where they’d lived for many years while Jesse was pursuing his surfing career, and decided that it would be a perfect family-friendly kind of establishment to run.

Nearly overnight, Surfin’ Spoon became an Outer Banks institution. As scions both of the local surfing community and the local Christian community, the Hineses had access to a built-in clientele that were streaming through the door before the paint was dry on the walls. In the months preceding its completion, almost every surfer in the water would ask Jesse, “Hey, when is your place opening up?” Now that they are open, business is booming.

With long shop hours and a baby boy to raise, Jesse’s had less time for surfing, but it hasn’t slowed him down. If anything, Jesse Hines is surfing better now than he ever has, and he always seems to strike at the peak two hours of any swell that’s on.

“I don’t have time to waste,” he says with a laugh. “I’m all like, I gotta pick up the kid in an hour, y’all stay out of my way so I can get my waves in.” And in that hour, he attacks the surf with a vengeance, screaming through barrels, launching off lips, and hitting backside snaps so hard you almost feel sorry for the water for taking such a beating.

Jesse takes flight under a mackerel sky. This was one of the showcase images in After the Storm, the original project that spawned Legends of the Sandbar. photo Chris Bickford

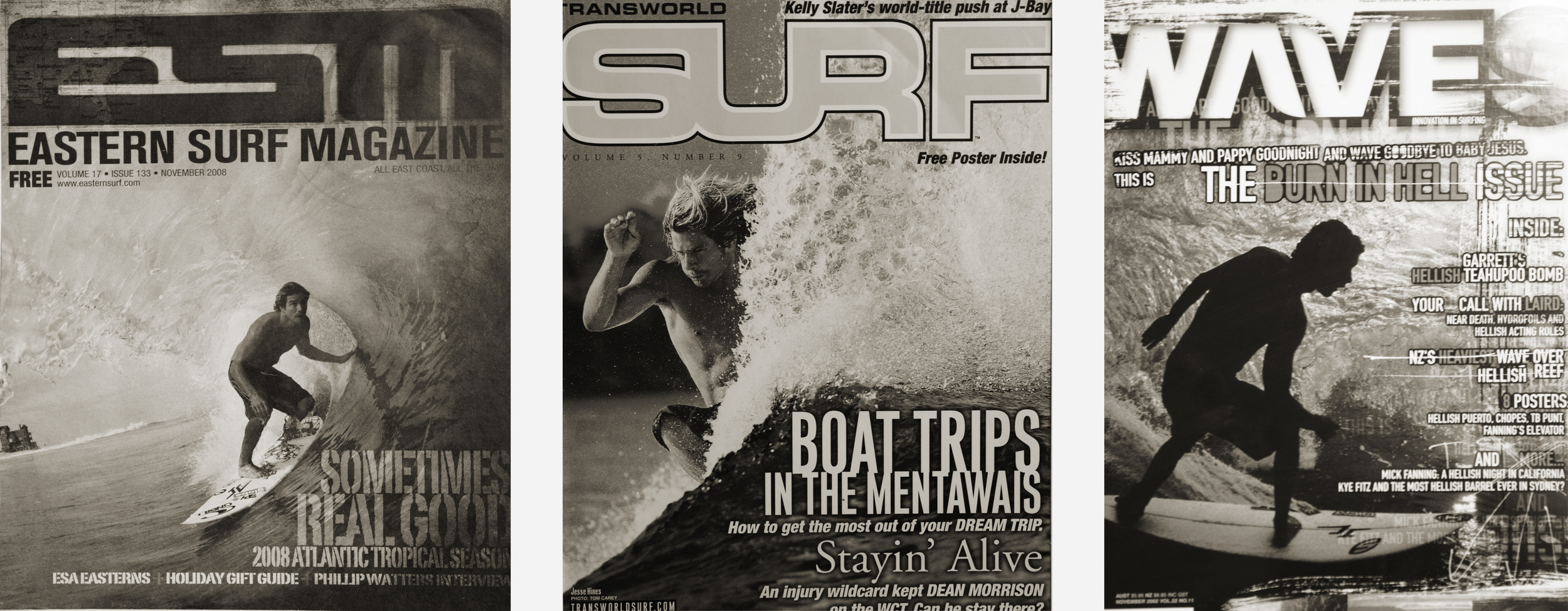

For those who live and surf on the Outer Banks, or who know anything about the surf world here, Jesse Hines needs little introduction. He’s a hometown hero who’s traveled the world, putting his sponsor’s O’Neill wetsuits through their paces in Alaska, Norway, Iceland, and other frigid locales. He’s been featured on the covers of Surfer Magazine, Surfing Magazine, Transworld Surf Magazine, and Eastern Surf Magazine. He’s braved the deserts of Oman and Yemen seeking exotic, unridden waves. And yes, for a brief run he was an international supermodel, a favorite of iconic fashion photographer Bruce Weber, who put his face and torso in magazines all over the world. Oh, and he also fronted a rock band. And has published two children's books (Sebi Goes Surfing and Sebi Gets Barreled, available at Surfin' Spoon and other local retailers).

Covers, Covers, Covers. At home or on the other side of the world, Jesse brings it. Photos: Tom Carey, Scott Aichner

But as impressive a resumé as that might appear, none of it comes as much of a surprise to anyone who knew Jesse growing up, as he was already a superstar on the Outer Banks before he took a crack at the big-time. And when forced by writers such as myself to re-hash the glories of his pro years, he tells his tales with such self-deprecating humor it’s clear that he’s never let any of it go to his head. For him it’s all a bit of an aw-shucks Mister-Smith-Goes-To-Washington odyssey, a story of a small-town boy who stumbled into some pretty cool stuff out in the big wide world before finally coming home to open up a yogurt shop. Which is a good attitude for an Outer Banker to have, because on these beaches, where “humble” is about the biggest compliment a hot-shot surfer can receive from his peers and elders, anyone who thinks they’re the shiz-nit because they got on the cover of a magazine will be razzed mercilessly by a pack of saltwater mongrels who take pride in the unique sense of obscurity that gives this place its mystique in the surfing world.

Jesse's first cover photo, age 13...or 14... photo courtesy Jesse Hines

Jesse Hines grew up on the Outer Banks, a born-and-bred surf junkie. His stepfather, legendary surfer and shaper Lynn Shell, fostered his growth as a surfer from an early age, and Jesse followed around rising local superstar Noah Snyder like an eager little brother. They both came of age with a pack of young rippers who ruled the peaks all up and down the beach, dominating the surf like no other crew had before them. Whatever spot was firing hardest, that’s where they would be. Children of the thruster revolution, they were never anything but new-school. Deep barrels, aggressive lip-smacks, boosting aerials -- it was all in a day’s fun for them. When it was on, they charged, and when it was off, they raged, uncontrollably. Living at the edge of the world in an outlaw culture of pirates and Peter Pans, they grew up loose, and they grew up fast. By all accounts, a little too fast. Things started getting tense among them. They’d get into fights, and some of them fell out with each other. Then, in the midst of their years of teenage rebellion, after too many hangovers and a growing sense of darkness about their lives, they began to gravitate, one by one, to a local church which was popular with some of the older surfers. And in a very short time, this fractured crew of young punks transformed into a stalwart cadre of die-hard born-again Christian surfers.

The Christian posse surfed with a newfound fervor. They gained strength from their shared devotion to their faith, to surfing, and to each other. It was the strangest of ironies, in a sport that tends to be associated more with a sex-drugs-and-rock’n’roll kind of lifestyle, that in the millennial years on the Outer Banks, it was cool to be a born-again Christian.

Though the zeal of those years has waned somewhat, the influence of that movement remains strongly felt on these shores, manifesting itself mostly in a common sense of virtue and compassion, a commitment to community, and an attitude of respect towards others. In a sport as competitive and localized as surfing, those sorts of qualities are too often missing. Along with a good dose of Southern gentility, the presence of Christian values in the water has kept the lineups on the Outer Banks, for the most part, friendly and free of the violence and aggression that plagues many of surfing’s more famous epicenters. Tempers may flare, but the watchful eyes of friends tend to keep even the most aggravated locals from taking anything to the beach but smiles and high-fives.

Local filmmaker Nic McLean’s documentary Noah’s Arc, centered around champion surfer and local legend Noah Snyder but also featuring the likes of Jesse, Matt Beacham, Brent McCoy, Brant Doyle, Jamie Smith, Barry Price Sr, and others, introduced this crew of East Coast Christian surfers to the world, and (alongside other features by parent studio Walking on Water) made mini-celebrities out of Noah, Matt, and Jesse. Opportunities soon followed. Sponsorship deals. Boat trips. Media spots. The future was wide open.

Jesse Gets the wave of the century on the Gulf Coast

Following Beacham’s lead, Jesse headed west to try his luck in the pro surfing media world. He was received with open arms, but he found out pretty quickly that getting sponsored and featured in magazines doesn’t exactly pay all the bills. “I’d get a travel budget, a small stipend, and a bunch of free stuff, and if I got into a magazine I’d get paid a few hundred bucks per photo. But added all up, it never really added up.” He’d make a little contest money here and there too, but just not enough to live on. At least not in California. It’s the paradox that a lot of artists and athletes live with: “famous” and “rich” don’t always go hand in hand.

So it was all a bit of a hustle. One week he’d be on a boat cruising through the Lafoten Islands of Norway, surfing against the backdrop of steep, snow-covered fjords, getting photographed for international surf publications, and the next few weeks he’d be on the Outer Banks, working a construction job. Then back out to California for a TV spot. As globe-trotting as his life was at the time, he’d still show up on random local swells, raising the bar of whatever crew might be out there chasing it. If you didn’t know he was traveling the world in the meantime, you’d think he was just hiding out like the rest of us, waiting for the waves to get good.

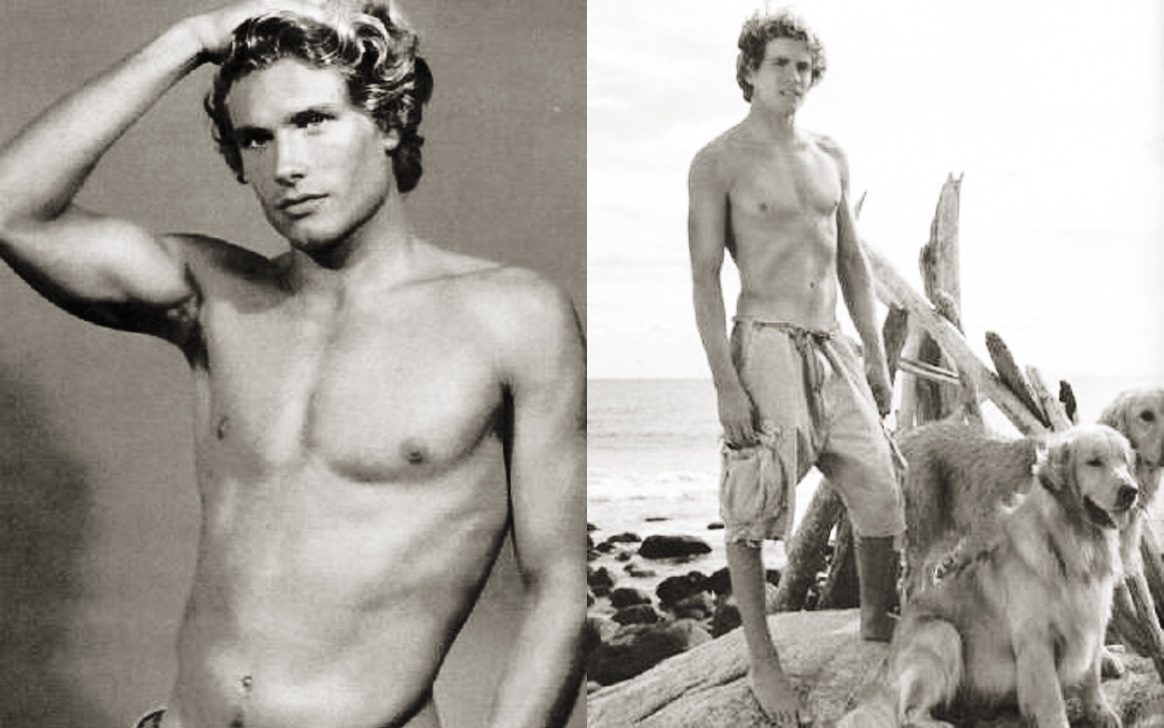

Still, it was tough to make ends meet. So, following Beacham’s suggestion, Jesse paid a visit to a modeling agent in California who specialized in the “surfer look”. Her advice to him? “Don’t cut your hair for six months, and go surfing every day. Get as tan and sunbleached as you can get, and I guarantee you Bruce Weber will hire you.”

Six months later he returned, his skin brown and buff, his hair positively Machado-esque. The agent took some polaroids. Within days he was on a set with fifty other guys and girls for a big Abercrombie campaign being shot by none other than Bruce Weber.

Weber, famous for making black-and-white shots of bare male torsos de rigeur in the fashion industry, was, at that time, pushing the limits of advertising and FCC regulations, and was trying to incorporate as much full-on nudity as his clients would allow; and since his photographic style had already transformed Abercrombie and Fitch into one of the hippest clothing brands in the world, they were giving him a lot of creative license.

“At the start of the shoot he told us that if we weren’t comfortable with nudity we shouldn’t be here, so I went up to him during a break and introduced myself and said, Mister Weber, it’s an honor to meet you, sir, and I respect what you’re doing, but I’m a Christian and I’m recently married and I’m just not cool with doing nude work, or making out with other girls or anything like that.” Weber gave him the usual lines that one could expect to hear from a powerful, ambiguously gay fashion photographer: that he was a beautiful man, that it would be a great experience for him, that he should open himself up to life’s possibilities. Et cetera. Jesse held his ground and Bruce decided to let him stay on. At the end of the week, Jesse was one of only a handful of models left. Weber had sent the rest of them packing. And over the course of the next several years Weber would call on Jesse again and again, taking him all over the world to model for top clothing labels. In the water and on the construction site, Jesse would get teased as “model-boy”, but he never turned down the work, as long as it was PG. The money was too good, and it was too much fun.

Model-boy working the magic. "I was always having to cinch up the pants they gave me because I'm so small. Most of the pants were 32 inches at the smallest sizes and I'm like a 30..." photos Bruce Weber

Then came the night, after a J. Crew shoot, at Weber’s house in Miami, where Bruce laid on the I’ll-take-you-to-the-top trip really hard, telling Jesse he could get him acting work in New York and take his career to the next level. Jesse politely declined the offer, explaining that that wasn’t what he wanted to do with his life. He was a surfer, and he wanted to surf. Whether Weber took it as a rejection of a magnanimous offer, or whether he found fresher faces to fuel his muse, isn't quite clear. But that was the last time Jesse got a call to model for Weber.

“I have nothing but respect and gratitude for Bruce,” Jesse says. “He’s a really brilliant and thoughtful guy, and it was an amazing opportunity. But in the end that just wasn’t my world, and I don’t think it could have gone any further than it went.”

Jesse had bigger problems to deal with, and they involved not the outside of his body, but the inside. Through all those years jetting back and forth to California and all around the world from there, Jesse had kept mum about a condition that could have easily ended his surfing career at any time. He was living with chronic pain, due to a metal rod that had been surgically attached to his right femur after a teenage automobile accident. As he grew and surfed and changed physically, the rod stayed in his leg and began to cause problems with his hip. From the age of 17 to the age of 31, when he finally had an operation to repair the bone and replace his hip, Jesse bit his lip and sucked it up, chomping down painkillers and waiting for the natural adrenaline high of the sport to kick in and take his mind off the metal grinding into his leg. The fact that during the entire course of his surfing career, when he was paddling into freezing slabs, landing big airs, suffering huge wipeouts, and contorting his body in extreme performance moves, he was fighting almost-debilitating chronic pain, makes his accomplishments all the more admirable. I wonder aloud to him what his career might have been like if he hadn’t had a bum leg.

“Honestly, I don’t think it would have been much different,” he says. “I wasn’t surfing contests or anything, and I just did the best I could. But you’ll notice all the cover shots of me are inside barrels, mainly because that was a position I could get into fairly easily without it causing too much pain.”

How that rod got put into his leg is the stuff of local lore, a tale often told at church testimonials and in surf magazines, as well as a major news story on the Outer Banks when it happened. Three teenage friends, driving home from Rodanthe after a day of chasing summer windswell. Crossing the notoriously unsafe Bonner bridge at Oregon Inlet, Matt Beacham, behind the wheel, suddenly and inexplicably, loses consciousness. Jesse, age 14, reaches forward from the backseat to try to steady the wheel, but not in time to avert an accident. The car swerves into the left lane, is sideswiped by an oncoming car, and gets launched onto the guardrail. With just enough of the vehicle’s weight on the the inside of the bridge to keep it from tumbling over the side, the boys are spared. Teetering over the edge of the guardrail, the truck is pried open with heavy machinery and the boys are pulled from the car by an EMT crew. As if to attest to the presence of a miracle, a license plate from another car in the pile-up is later found in the back seat of the boys’ SUV, the frame around it saying, “In God we Trust”.

Few people have a more complicated history with the Bonner Bridge than Jesse Hines. It's brought him countless days of joy and many years of pain. photo Chris Bickford

That’s often where the story ends. But for Jesse it was just the beginning of a very long struggle to overcome his injuries. His femur was broken, his hip sockets shattered, and because he was a minor, the EMT responders were unable to administer anesthesia to him without parental consent.

“This was before the days of cell phones,” Jesse says. “My mom didn’t even know it had happened until about six hours later.” By that time Jesse had been helicoptered to Sentara hospital in Norfolk, screaming in agony. While he waited for his mom to show up, he was placed in an IC unit, still with no anesthetics.

“I remember just groaning constantly, and then I found that if I hit this one particular tone, the pain would subside somewhat, so I just kept groaning that note, holding it for as long as I could. But there was another guy in the room, separated by a curtain, and he kept going, ‘stop groaning, you’re driving me crazy!’”

It was over eight hours between the time of the accident and the time Jesse’s mom was able to complete the consent form to administer anesthesia. After that, Jessie was given a choice: they could set the broken bones and put him in a body cast for six months, or they could secure his femur with a metal rod and he’d be able to walk and surf again in a few weeks. Jesse, being young and surf-stoked, chose the latter option. As soon as his hip sockets healed, he was back in the water.

Three years later, the pain started coming back. His doctor told him he was just going to have to live with it, unless he wanted another operation. “He was like, you’re young, you like to surf, I’m sure you don’t want to have to get an operation and sit around for the next six months in a cast.

“In retrospect, I should have gotten a second opinion.”

When at the age of thirty he finally started looking into getting surgery, Jesse’s doctor told him that his hip X-ray looked like that of a ninety-year-old woman. It was time to bite the bullet. He had the operation he’d been putting off his entire adult life.

The global financial crisis forced the issue. Major surf brands were forced to downsize their operations, and team riders like Jesse were the first to go. He lost his longtime sponsorship from O'Neill, which effectively ended his career as a pro surfer. "I was pretty upset at first, because I worked really hard for them, but in the end it was just about the economics, so I just had to roll with it."

So, Jesse adapted, and took advantage of the change. He scheduled the operation, and he and Whitney acquired an old oceanside building in Nags Head, once the site of the former Jockey's Ridge Restaurant, and began transforming it into Surfin' Spoon.

It just so happened that Noah Snyder was getting a hip replacement as well, and their operations fell within days of each other. Post-op, the two of them could be seen out in the water together with bodysurfing wedges, categorically unable to stay on dry land when there were waves to ride.

But most of Jesse's time was spent wearing a tool belt, as he and Whitney worked on the new shop. And then, shortly after they opened, Whitney got pregnant. And in due time, Bear was born. A new leg, a new business, a new family, a new life. And a lot of diapers to change.

Jesse Hines's story is far from over. The greatest adventure of all, being a dad, has just begun. And with the ocean just yards from his shop and a whole extended family on hand to help out, it's unlikely Jesse will miss a hometown swell anytime soon. As long as he's back in time to man the shop, or pick up Bear, or place an order for more M&M's. He's still playing music at church, and once Bear is old enough to travel, there may be some serious off-season adventures ahead.

We'll just have to wait and see. In the meantime, be careful with those chocolate-with-sea-salt chunks. They're addictive.

One happy yogurt-eatin' family: Whitney, Bear and Jesse. photo Chris Bickford